Case study - Creating hīnaki

Students at Newton Central School build hīnaki prior to going on school camp

About this resource

A case study of classroom practice, demonstrating opportunities for technology teaching and learning that are place-based and that connect with real-world contexts and mātauranga Māori.

Case study - Creating hīnaki

Year levels: 6, 7, 8

Curriculum levels: 3, 4

Learning phases: Years 4-6, Years 7-8

Technological area: Designing and developing materials outcomes

Technology strands: Technological Practice, Technological Knowledge (While these were the focus, this unit includes all three strands)

Achievement objective: Outcome Development and Evaluation

School: Newton Central School

Teacher: Ruth Lemon

Mātauranga Māori: Constructing a hīnaki, materials from Te Taiao, tikanga about tuna (eels), sociocultural importance of tuna. See Want To Try Something Like This Yourself section for more suggestions.

Enduring understanding: assessing and critiquing materials outcomes in terms of quality of design and fitness for purpose, can create outcomes that solve real-world problems.

Students from Newton Central School in central Auckland developed hīnaki (eel traps) using modern materials in a unit that offered a rich context for technology design and development that required students to connect with te ao Māori, including mātauranga Māori and tikanga Māori.

Mātauranga Māori offers many rich opportunities for exploring many of the areas and strands of the technology curriculum. Tūpuna had knowledge of the local environment and how to survive and thrive in Aotearoa New Zealand. In this showcase students research the construction of hīnaki and then engage in building prototypes, testing, and revising their design.

Teacher Ruth Lemon describes how the project came about: "We were building up to a year 6 to 8 leadership camp at Kokako Lodge in West Auckland, so we got the tuākana (seniors) to investigate using things in the camp area, and their research showed there was potential for catching tuna (eels)."

Learning intentions could be that students will:

- design a hīnaki to catch tuna

- create a prototype and test

- refine their design and trial it.

The students first studied a completed hīnaki that Ruth brought into class, taking note of its structural and material properties. Research was then carried out on the traditional materials, techniques, and processes for creating hīnaki, as well as the sociocultural importance of tuna both in New Zealand and overseas.

The students' research involved talking with teachers, local experts, and internet searches.

Each student developed individual design drawings for a proposed hīnaki and shared their designs in groups of four or five, working together to refine their ideas until each group agreed on a final design.

"First they had to figure out how they would secure one end of the hīnaki with a hinge so that they would be able to first bait the trap, then get the eel out, while the other side needed to be firmly attached and have a funnel that the eel would go through.”

The funnel was an extremely important part of the hīnaki design – too thin, and the tuna wouldn't be able to get inside; too wide, and the tuna would be able to escape after eating the bait.

Hīnaki are traditionally made with kareao (supplejack), a twisting vine found in lowland forests, but as this wasn't readily available the groups carried out online research into the best modern materials for the job.

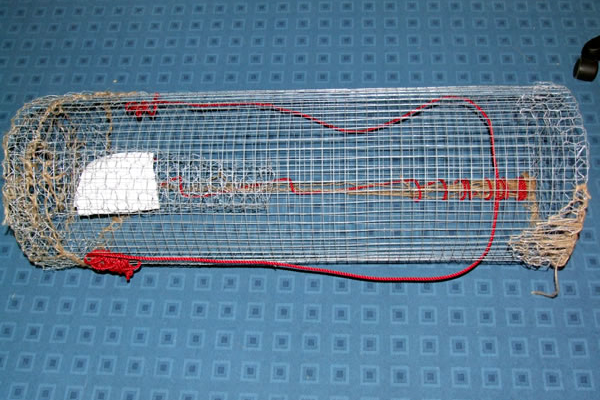

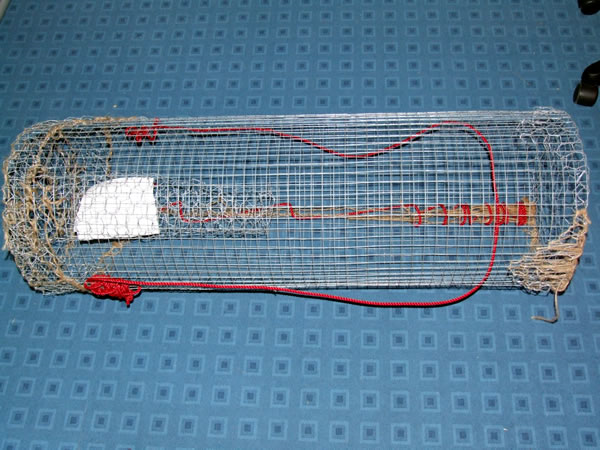

Although each group had differences in their designs, the main materials chosen were a variety of wire mesh sourced from The Warehouse. For stronger structural elements, such as the outer cylinder of the trap, some groups used galvanised 2.5 cm steel mesh. For more intricate elements, such as the funnel and the hinged doors of the trap, thinner chicken-wire mesh was chosen for its increased flexibility.

Designs and materials ready, the students began construction of their prototypes. Using wire cutters, the students cut the lengths of wire mesh they needed to form the main tube of their hīnaki. To form the tube, the groups first bent the end of the wires with pliers so that the two sides could hook together. The students then reinforced this connection with strong cord, winding it through the gaps in the mesh along the entire length of the tube. The funnel and end hinge were more intricate components and the students went through a period of trial-and-error, cutting and refitting the chicken-wire until it functioned correctly.

The students then tested the strength of their traps. Without access to a river at the school the students came up with some imaginative solutions.

"The students' thinking was that if the hīnaki could stand up to a high-pressure hose then it would be able to stand up to the river currents", Ruth says. "They also threw them around a little bit on the school field".

The students found that some parts of their traps were failing under the strain, so extra wire and cord was used on the seams and hinges to reinforce the strength of the traps.

Once their hīnaki were completed, the students researched the best bait for the traps. Any bait the students used would have to be easy to place in the trap, attract the tuna from a distance and not dissolve too quickly in the water. Most of the students decided on a mixture of bacon and bloodworms though dog roll was also trialled by some groups.

At the end of term, the class arrived at Kokako Lodge eager to trial their hīnaki in the nearby stream. The students first placed their bait in a tied-up plastic bag with puncture holes. This kept the bait secure in the hīnaki while allowing the scent of the bait into the stream to attract the tuna.

The students then carefully placed their hīnaki in the stream, secured them in place with ropes so they could be hauled to shore later, and left them there overnight.

The following day the students found that two of the hīnaki successfully caught tuna, one was empty, and another had been swept out to sea.

"The rope that group used wasn't strong enough so they were very sad about that", Ruth says. "But the key things the students came back to me with was that in future they needed to make a foolproof system for securing it to the riverbank and that the funnel on one of the traps might have been too small for the eels to get in".

Though disappointed, the groups that didn't trap any tuna decided to extend the project using other forms of fishing they had discovered in their research.

"One method was similar to a hook-and-line. They also tried a stick with a hook fashioned onto it that was more like a spear and two of our boys managed to catch something with it".

Once all the tuna were retrieved, the students were taught how to skin and prepare the tuna for eating by teacher Anaru Martin. The tuna were then smoked and eaten by the whole class.

Ruth reports that preparing the tuna was a real highlight for the students at the end of the project. "I think they were also pretty stoked to see that their traps actually worked".

This unit emerged from opportunities created by the upcoming school camp, and the potential to catch tuna while on camp (refer to EOTC guidelines). By focusing the learning on researching, designing and building hīnaki, this unit enabled students in Aotearoa New Zealand to develop technological knowledge, understanding, and skills that also required connecting with te ao Māori, including mātauranga Māori and tikanga Māori.

Other possibilities for extending learning include the following:

- Investigating local pūrākau and mātauranga about tuna and connecting with whānau and hapū to hear their stories of catching, harvesting, and eating tuna.

- Researching local hapū/iwi maramataka and learning about the lunar cycle. Investigating and testing the best times to catch tuna according to the maramataka.

- Inviting students to share their knowledge and cultural traditions about tuna, and exploring traditional stories and practices from other nations, e.g., Pacific nations, South-east Asia, etc.

- Iniviting students to compare the advantages and disadvantages of their hīnaki made with modern materials with one made with traditional materials

- Iniviting students to make other traditional food and catch and/or food storage items.

- Learning about tuna habitats and life-cycles, and why the long-finned eel are classified as ‘at risk declining’ in Aotearoa New Zealand.

If catching tuna please check with local hapū and iwi around the kawa (protocols) around catching tuna. Consideration of the status (e.g. at risk) of the tuna in the rohe is essential, as is correct identification of the species of tuna.

Museums - check out the resources in your local museums and online museum resources.

The Long Swim - Ready to Read phonics book, curriculum level 1

The Village Beach - School Journal Level 3, November 2017

Hīnaki - eel pots - summary on Te Ara

Preparing a Hīnaki - YouTube clip by Te Papa Tongarewa

Taonga Species Series: Tuna and Tuna - information from NIWA

Restoring Tuna- a guide for the Waikato and Waipā Catchments - information from Waikato River Authority

Kaitiakitanga - activities related to being kaitiaki for a local awa; includes suggestions for the digital technologies areas and all three strands

Tuna-Ngāi Tahu Mahinga Kai - YouTube video

He reo tō te tuna - YouTube video