NZC - English (Phase 1)

Progress outcome and teaching sequence for Phase 1 (year 0-3) of the English Learning Area. From 1 January 2025 this content is part of the statement of official policy relating to teaching, learning, and assessment of English in all English medium state and state-integrated schools in New Zealand.

NZC – English |

NZC – English Phase 1 – Years 0‑3 |

NZC – English |

About this resource

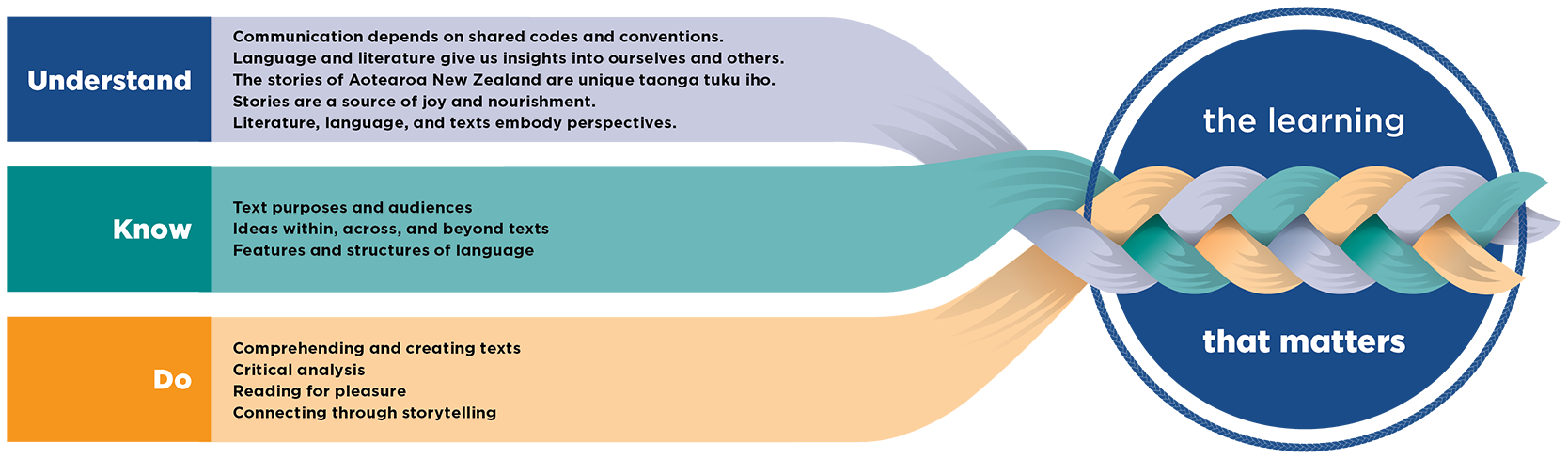

This page provides the progress outcome and teaching sequence for Phase 1 (Year 0-3) of the English learning area of the New Zealand Curriculum, the official document that sets the direction for teaching, learning, and assessment in all English medium state and state-integrated schools in New Zealand. In English, students study, use, and enjoy language and literature communicated orally, visually, or in writing. It comes into effect on 1 January 2025. Other parts of the learning area are provided on companion pages.

We have also provided the English Year 0-6 curriculum in PDF format. There are different versions available for printing (spreads), viewing online (single page), and to view by phase. You can access these using the icons below. Use your mouse and hover over each icon to see the document description.